A Study of WebRTC Security

Abstract

Web Real-Time Communication (abbreviated as WebRTC) is a recent trend in web application technology, which promises the ability to enable real-time communication in the browser without the need for plug-ins or other requirements. However, the open-source nature of the technology may have the potential to cause security-related concerns to potential adopters of the technology. This paper will discuss in detail the security of WebRTC, with the aim of demonstrating the comparative security of the technology.

1. Introduction

WebRTC is an open-source web-based application technology, which allows users to send real-time media without the need for installing plugins. Using a suitable browser can enable a user to call another party simply by browsing to the relevant webpage.

Some of the main use cases of this technology include the following:

- Real-time audio and/or video calls

- Web conferencing

- Direct data transfers

Unlike most real-time systems (e.g. SIP), WebRTC communications are directly controlled by some Web server, via a JavaScript API.

The prospect of enabling embedded audio and visual communication in a browser without plugins is exciting. However, this naturally raises concerns over the security of such technology, and whether it can be trusted to provide reliable communication for both the end users and any intermediary carriers or third parties.

This report will address these topics and examine the protections that WebRTC provides to provide security in all cases. For the purposes of this paper however, native applications will be treated as being out of scope.

2. Overview of WebRTC Architecture

WebRTC enables direct media-rich communication between two peers, using a peer-to-peer (P2P) topology. WebRTC resides within the user's browser, and requires no additional software to operate. The actual communication between peers is prefaced by an exchange of metadata, termed "signalling". This process is used to initiate and advertise calls, and facilitates connection establishment between unfamiliar parties.

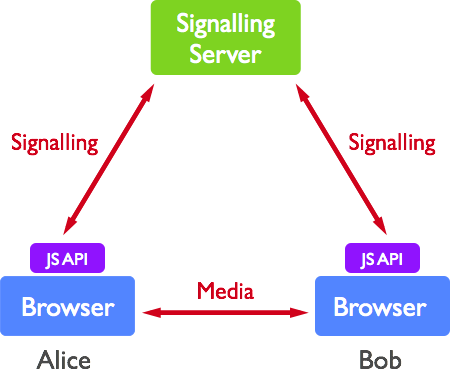

As depicted in Figure 1, this process occurs through an intermediary server:

Figure 1. A simple WebRTC Call Topology

A signaling protocol is not specified within WebRTC, allowing developers to implement their own choice of protocol. This allows for a deeper degree of flexibility in adapting a WebRTC app for a specific use case or scenario.

How does WebRTC communication work?

WebRTC relies on three APIs, each of which performs a specific function in order to enable real-time communication within a web application. These APIs will be named and explained briefly. The implementation and technical details of each protocol and technology are outside the scope of this report, however the relevant documentation is readily available online.

getUserMedia

For many years it was necessary to rely on third-party browser plugins such as Flash or Silverlight to capture audio or video from a computer. However, the era of HTML 5 has ushered in direct hardware access to numerous devices, and provides JavaScript APIs which interface with a system's underlying hardware capabilities.

getUserMedia is one such API, enabling a browser to access a user's camera and microphone. Although utilised by WebRTC, this API is actually offered as part of HTML 5.

RTCPeerConnection

RTCPeerConnection is the first of two APIs which are offered specifically as part of the WebRTC specification. A RTCPeerConnection interface represents the actual WebRTC connection, and is relied upon to handle the efficient streaming of data between two peers.

When a caller wants to initiate a connection with a remote party, the browser starts by instantiating a RTCPeerConnection object. This includes a self-generated SDP description to exchange with their peer. The recipient in turn responds with its own SDP description. The SDP descriptions are used as part of the full ICE workflow for NAT traversal.

With the connection now established, RTCPeerConnection enables the sending of real-time audio and video data as a bitstream between browsers.

Ultimately, RTCPeerConnection API is responsible for managing the full life-cycle of each peer-to-peer connection and encapsulates all the connection setup, management, and state within a single easy-to-use interface.

RTCPeerConnection has two specific traits: - Direct peer-to-Peer communication between two browsers - Use of UDP/IP - there is no guarantee of packet arrival (as in TCP/IP), but there is much reduced overhead as a result. - (By allowing the loss of some data, we can focus upon offering real-time communication.)

RTCDataChannel

The RTCDataChannel is the second main API offered as part of WebRTC, and represents the main communication channel through which the exchange of arbitrary application data occurs between peers. In other words, it is used to transfer data directly from one peer to another.

Although a number of alternative options for communication channels exist (e.g. WebSocket, Server Sent Events), however these alternatives were designed for communication with a server rather than a directly-connected peer. RTCDataChannel resembles the popular WebSocket, but instead takes a peer-to-peer format while offering customisable delivery properties of the underlying transport.

2.1. Underlying Technologies

The three main APIs are the developer-facing aspects of WebRTC, but there are a number of foundational technologies which are utilised in order to provide these protocols (the RTCPeerConnection and RTCDataChannel APIs).

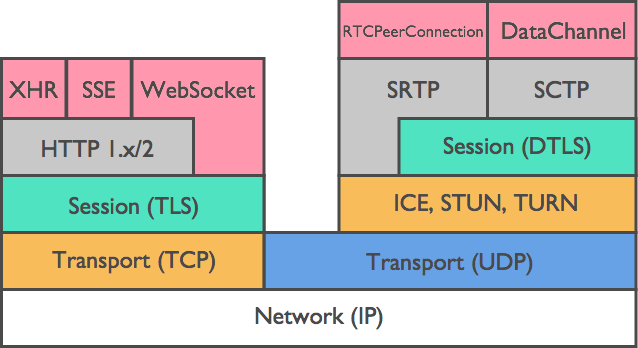

Figure 2. WebRTC Protocol Stack

ICE, STUN, and TURN are necessary to establish and maintain a peer-to-peer connection over UDP. DTLS is used to secure all data transfers between peers, as encryption is a mandatory feature of WebRTC. Finally, SCTP and SRTP are the application protocols used to multiplex the different streams, provide congestion and flow control, and provide partially reliable delivery and other additional services on top of UDP.

SDP: Session Description Protocol

Session Description Protocol (SDP) is a descriptive protocol that is used as a standard method of announcing and managing session invitations, as well as performing other initiation tasks for multimedia sessions. SDP represents the browser capabilities and preferences in a text-based format, and may include the following information: - Media capabilities (video, audio) and the employed codecs - IP address and port number - P2P data transmission protocol (WebRTC uses SecureRTP) - Bandwidth usable for communication - Session attributes (name, identifier, time active, etc.) -> However these are not used in WebRTC. - Other related metadata...

As of today SDP is widely used in the contexts of Session Initiation Protocol (SIP), Real-time Transport Protocol (RTP), and Real-time Streaming Protocol (RSP).

References: [3]

ICE: Interactive Connectivity Establishment

Signalling requires the initial use of an intermediary server for the exchange of metadata, but upon completion WebRTC attempts to establish a direct P2P connection between the users. This process is carried out through the ICE framework.

ICE is a framework used for establishing a connection between peers over the internet. Although WebRTC tries to utilise direct P2P connections, in reality the widespread presence of NAT (Network Address Translation) makes it difficult to negotiate how two peers will communicate.

Due the continuing widespread prevalence of IPv4 addresses with their limited 32-bit representation, most network-enabled devices do not have a unique public-facing IPv4 address with which it would be directly visible on the Internet. NAT works by dynamically translating private addresses into public ones when an outbound request passes through them. Similarly, inbound requests to a public IP are converted back into a private IP to ensure correct routing on the internal network. Resultantly, sharing a private IP is often not enough information to establish a connection to a peer. ICE attempts to overcome the difficulties posed by communicating via NAT to find the best path to connect peers.

By trying all possibilities in parallel, ICE is able to choose the most efficient option that works. ICE first tries to make a connection using the host address obtained from a device's operating system and network card; if that fails (which it inevitably will for devices behind NATs) ICE then obtains an external address using a STUN server. If that also fails, traffic falls back to routing via a TURN relay server.

The candidate communication routes are rendered in a text-based format, and the list ordered by priority. The options take the form of one of the following: - Direct P2P communication - Using STUN, with a port mapping for NAT traversal (This route eventually resolves to direct P2P communication) - Using TURN as an intermediary (this configuration employs relayed communication rather than P2P)

Out of all possible candidates, the route with the smallest overhead is chosen.

References: [4]

STUN: Session Traversal Utilities for NAT

In order to perform P2P communication, both parties necessarily require at least the knowledge of their peer's IP address and the assigned UDP port. As a result, a certain amount of information exchange is necessary before WebRTC communication can be established.

A STUN server is used by each peer to determine their public IP address, and is referenced by the ICE framework during connection establishment. STUN servers are typically publically accessible, and can be used freely by WebRTC applications.

TURN: Traversal Using Relays around NAT

In the eventuality that establishing a P2P communication fails, a fallback option can be provided via a TURN server. By relaying traffic between peers the WebRTC communication can be ensured, but can suffer degradations in media quality and latency.

TURN servers can ensure high success in setting up calls, regardless of the end-user's environments. As the data is sent through an intermediary server, server bandwidth is also consumed. If many calls are simultaneously routed through the server, the bandwidth was also become considerable in size.

The server itself is typically not freely accessible, and has to be specifically provided (or rented) by the application provider.

3. Browser-based Security Considerations

There are a number of ways in that a real-time communication application may impose security risks, both on the carrier and the end users. Such security risks can be applicable to any application which deals with the transmission of real-time data and media.

WebRTC differs from other RTC apps by providing a strong and reliable infrastructure for even new developers to utilise without compromising on security. We will now proceed to discuss how WebRTC deals with each of these risks in turn.

References: [5]

3.1. Browser Trust Model

The WebRTC architecture assumes from a security perspective that network resources exist in a hierarchy of trust. From the user's perspective, the browser (or user client) is basis of all WebRTC security, and acts as their Trusted Computing Base (TCB).

The browser's job is to enable access to the internet, while providing adequate security protections to the user. The security requirements of WebRTC are built directly upon this requirement; the browser is the portal through which the user accesses all WebRTC applications and content.

While HTML and JS provided by the server can cause the browser to execute a variety of actions, the browser segregates those scripts into sandboxes. Said sandboxes isolate scripts from each other, and from the user's computer. Generally speaking, scripts are only allowed to interact with resources from the same domain - or more specifically, the same "origin".

The browser enforces all security policies that the user desires and is the first step in the verification of all third parties. All authenticated entities have their identity checked by the browser.

If the user chooses a suitable browser which they know can trust, then all WebRTC communication can be considered "secure" and to follow the standard accepted security architecture of WebRTC technology. However, if there is any doubt that a browser is "trustable" (e.g. having been downloaded from a third party rather than a trusted location), then all following interaction with WebRTC applications is impacted and may not be reliably secure.

In other words, the level of trust provided to the user by WebRTC is directly influenced by the user's trust in the browser.

3.2. SOP: Same Origin Policy

It is a fundamental aspect of the DOM that all webpage resources are fetched from the page's web server, whenever some or all of the page is loaded. Fetching of resources takes place either when a page is freshly loaded by the browser, or when a script residing on a webpage makes such a request. Such scripts are readily able to make HTTP requests via e.g. the XMLHttpRequest() API, but are not permitted to make such requests to just any server they specify. Rather, requests have to be made to the same "origin" from where the script originated. An "origin" comprises of a URI scheme, hostname, and port number. This overall restriction is termed the "Same Origin Policy" (SOP).

SOP forces scripts to execute in isolated sandboxes specific to their originating domain, therefore preventing pages from different origins or even iframes on the same page from exchanging information. Webpages and scripts from the same origin server remain unhindered in interacting with each other’s JS variables. As such, the origin constitutes the basic unit of web sandboxing.

Through enforcing execution sandboxes on a per-origin basis, the end user is protected from the misuse of their credentials. You would reasonably expect to safely use a social networking website without a script executing from within an advertisement panel and stealing your login information.

Similarly, the servers of e.g. the webpage provider are protected from attacks mounted via the user's browser; If such safeguards did not exist, DoS attacks could otherwise be launched through abusive resource requests.

References: [6]

3.2.1 Bypassing SOP

SOP is incredibly important for the security of both the user and web servers in general, although it does have the disadvantage of making certain types of web app harder to create. Methods of permitting inter-site interaction do exist, although these are typically mutually consensual and limited to certain channels.

The W3C Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) spec is one of the answers to the problem. It allows the browser to contact the script's target server to determine whether it is willing to participate in a given type of transaction. As such, cross-origin requests can be safely allowed, by giving the target server the option to specifically opt-in to certain requests and decline all others.

WebSockets is another option allowing similar functionality, but on transparent channels rather than isolated HTTP requests. Once such a connection has been established, the script can transfer traffic and resources as it likes, with the necessity of framing as a series of HTTP request/response transactions.

In both cases, the initial verification stage prevents the arbitrary transfer of data by a script with a different origin.

4. WebRTC Security Considerations

References: [7]

4.1. Installation and Updates

A prevalent issue with traditional desktop software is whether one can trust the application itself. Installation of new software or a plugin can potentially surreptitiously install malware or other undesirable software. Many end users have no idea where the software was made or exactly who they are downloading the app from. Malicious third parties have had great success in repackaging perfectly safe and trusted software to include malware, and offering their custom package on free software websites.

WebRTC however is not a plugin, nor is there any installation process for any of its components. All the underlying WebRTC technology is installed simply as part of downloading a suitable WebRTC-compatible browser, such as Chrome or Firefox. If a user has such a browser, they can browse to and use any WebRTC application with no other setup or preparation required. As such there is no risk of installation of malware or viruses through the use of an appropriate WebRTC application. However, WebRTC apps should still be accessed via a HTTPS website signed by a valid authenticator such as Verisign.

Another related consideration is the patching of discovered security flaws in software. As with any software technology, it is entirely possible that future bugs or vulnerabilities will be discovered in WebRTC. If a vulnerability is found in a traditional desktop application (such as a typical VoIP application), development of a patch may take considerable time. This is a frequent issue with application development, as security is still often treated as a secondary consideration after functionality. Going deeper than this, we can contemplate hardware-based communication methods. How often does a VoIP phone get a security update? Can you trust the person responsible to update it regularly? Do you even know who is responsible?

Contrary to this, browsers are a fast-paced development scene due to the frequency and range of risks users are exposed to, as well as their ubiquitous nature (and the importance of information accessed through the browser). As WebRTC's components are offered as part of a browser, they are likewise updated whenever the browser is updated. If a future vulnerability were to be found in a browser's WebRTC implementation, a fix will likely be delivered rapidly. This can particularly be seen to be true in Chrome and Firefox's rapid development cycles. In fact, in the era of automatic updates, WebRTC components can be updated through a new browser version as soon as the patch is made available on servers. Most modern browsers have a good record of auto-updating themselves within 24 hours of the discovery of a serious vulnerability or threat.

As a side note: Although we have stated that WebRTC requires no plugins to be installed, it is possible that third-party WebRTC frameworks may offer plugins to enable support on currently unsupported browsers (such as Safari and IE). User caution (or a supported browser) is recommended in such instances.

4.2. Access to Media/Local resources

The browser can access local resources (including camera, mic, files), which leads the inevitable concern of a web application accessing a user's microphone and camera. If web applications could freely gain access to a user's camera or microphone, an unscrupulous app may attempt to record or distribute video or audio feeds without the user's knowledge. It could be a simple matter for a website residing in a background tab to abuse the user's trust (the user may not even realise a site harbours such a communication application).

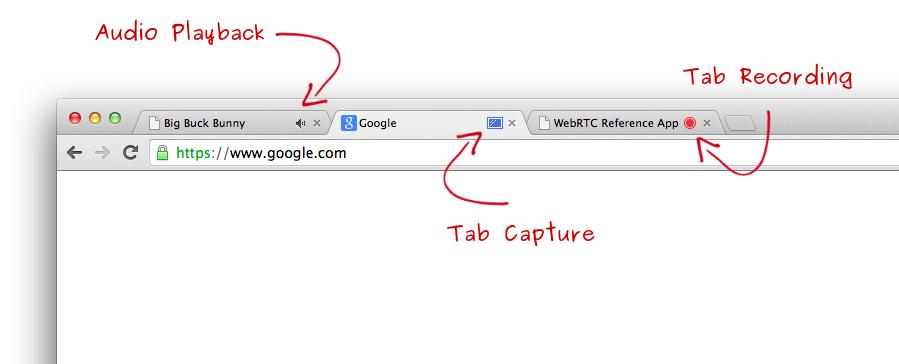

WebRTC combats this by requiring the user to give explicit permission for the camera or microphone to be used (both can be configured individually). It is possible to ask the user for one-time or permanent access. It is not possible for a WebRTC application to arbitrarily gain access or operate either device. Furthermore, when either the microphone or camera is being used the client UI is required to expressly show the user that the microphone or camera are being operated. In Chrome, this takes the form of a red dot on any tab accessing a user's media.

Figure 3. Chrome UI Indicators

The philosophy of this security protection is that a user should always be making an informed decision on whether they should permit a call to take place, or to receive a call. In other words, a user must understand: - Who or what is requesting access to his media - Where the media is going - Or both.

As an additional provision, the WebRTC spec specifies that browsers SHOULD stop the camera and microphone when the UI indicator is masked (e.g. by window overlap). Although this is more of an ideal behaviour, it isn't necessarily guaranteed and users should exercise caution. Fortunately, however, this additional functionality is not likely to be behaviour expected by the user.

Screen sharing introduces further security considerations due to the inherent flexibility of scope. A user may not be immediately aware of the extent of the information that they are sharing. For instance, they may believe they are simply sharing a stream of a particular window (e.g. while giving a presentation to remote parties), when in reality they are showing their entire screen to their audience. This may be a result of the user failing to correctly establish the initial screen sharing setup, or else that the user may simply forget the extent of what they are sharing.

4.3. Media Encryption & Communication Security

There are a number of ways in that a real-time communication application may impose security risks. One particularly notable one is the interception of unencrypted media or data during transmission. This can occur between browser-browser or browser-server communication, with an eavesdropping third-party able to see all data sent. Encryption however, renders it effectively impossible for an eavesdropper to determine the contents of communication streams. Only parties with access to the secret encryption key can decode the communication streams.

Encryption is a mandatory feature of WebRTC, and is enforced on all components, including signaling mechanisms. Resultantly, all media streams sent over WebRTC are securely encrypted, enacted through standardised and well-known encryption protocols. The encryption protocol used depends on the channel type; data streams are encrypted using Datagram Transport Layer Security (DTLS) and media streams are encrypted using Secure Real-time Transport Protocol (SRTP).

4.3.1. DTLS: Datagram Transport Layer Security

WebRTC encrypts information (specifically data channels) using Datagram Transport Layer Security (DTLS). All data sent over RTCDataChannel is secured using DTLS.

DTLS is a standardised protocol which is built into all browsers that support WebRTC, and is one protocol consistently used in web browsers, email, and VoIP platforms to encrypt information. The built-in nature also means that no prior setup is required before use. As with other encryption protocols it is designed to prevent eavesdropping and information tampering. DTLS itself is modelled upon the stream-orientated TLS, a protocol which offers full encryption with asymmetric cryptography methods, data authentication, and message authentication. TLS is the de-facto standard for web encryption, utilised for the purposes of such protocols as HTTPS. TLS is designed for the reliable transport mechanism of TCP, but VoIP apps (and games, etc.) typically utilise unreliable datagram transports such as UDP.

As DTLS is a derivative of SSL, all data is known to be as secure as using any standard SSL based connection. In fact, WebRTC data can be secured via any standard SSL based connection on the web, allowing WebRTC to offer end-to-end encryption between peers with almost any server arrangement.

References: [8]

4.3.1.1. DTLS over TURN

The default option for all WebRTC communication is direct P2P communication between two browsers, aided with signalling servers during the setup phase. P2P encryption is relatively easy to envisage and setup, but in the case of failure WebRTC setup falls back to communication via a TURN server (if available). During TURN communication the media can suffer a loss of quality and increased latency, but it allows an "if all else fails" scenario to permit WebRTC application to work even under challenging circumstances. We must also consider encrypted communication under TURN's alternative communication structure.

It is known that regardless of communication method, the sent data is encrypted at the end points. A TURN server's purpose is simply the relay of WebRTC data between parties in a call, and will only parse the UDP layer of a WebRTC packet for routing purposes. Servers will not decode the application data layer in order to route packets, and therefore we know that they do not (and cannot) touch the DTLS encryption.

Resultantly, the protections put in place through encryption are therefore not compromised during WebRTC communication over TURN, and the server cannot understand or modify information that peers send to each other.

4.3.2. SRTP: Secure Real-time Transport Protocol

Basic RTP does not have any built-in security mechanisms, and thus places no protections of the confidentiality of transmitted data. External mechanisms are instead relied on to provide encryption. In fact, the use of unencrypted RTP is explicitly forbidden by the WebRTC specification.

WebRTC utilises SRTP for the encryption of media streams, rather than DTLS. This is because SRTP is a lighter-weight option than DTLS. The specification requires that any compliant WebRTC implementation support RTP/SAVPF (which is built on top of RTP/SAVP) [9]. However, the actual SRTP key exchange is initially performed end-to-end with DTLS-SRTP, allowing for the detection of any MiTM attacks.

4.3.3. Establishment of a secure link

Let us step through the process of establishing a new call on a WebRTC application. In this instance, there will be two parties involved; Alice and Bob. The call procedure is initiated when one party (Alice) calls the other (Bob), and the signalling process exchanges the relevant metadata between both parties.

Once the initial ICE checks have concluded (or specifically, some of them), the two peers will start to setup one or more secure channels. Initially, a DTLS handshake is performed on all channels that are established by ICE. For the data channels, this step alone is sufficient as plain simple DTLS is used for encryption. For the media channels however, further steps are taken.

Once the DTLS handshake completes, the keys are "exported" and used to key SRTP for the media channels. At this stage both parties know that they share a set of secure data and/or media channels with keys which are not known to any malicious third-party.

References: [10]

4.3.4. DTLS-SRTP vs SDES

In order to negotiate the security parameters for the media traffic session, SRTP needs to interact with a key management protocol. This protocol is not established, offering up a number of possible options for the task. Two such options are SDES and DTLS-SRTP.

It is worth noting that the signalling (SIP, HTTP) & media (RTP) involved in a multimedia communication can be secured independently.

SDES

SDP Security Descriptions for Media Streams (SDES) was the option previously favoured by WebRTC.

Within SDES, the security parameters and keys used to set up SRTP sessions are exchanged in clear text in the form of SDP attributes. As SDP is communicated over the signalling plane, if encryption is not additionally enacted upon such signalling messages then an eavesdropping third party could obtain the keys for the SDES encrypted data. In other words, a further encryption protocol should be utilised specifically for the encryption of the signalling plane. One such option for this is to use TLS.

Securing the signalling and media independently however, can lead to the situation in that the media user is different from the signalling user (as no guarantee is provided). To provide this guarantee, a cryptographic binding is necessary. DTLS-SRTP is one such mechanism that provides this, but SDES does not.

It remains a fact that even today, the majority of RTP traffic in VoIP networks is not secured. In fact, encryption is one of the very first features customers usually ask vendors to remove in order to meet their budgets. When secured, most of the deployments utilise SDES, which as we just mentioned relies heavily on signalling plane security.

DTLS-SRTP

DTLS-SRTP on the other hand exchanges keys over the media plane, rather than the signalling plane. The consequence of such a difference is that an SRTP media channel has no need to reveal the secret encryption keys through an SDP message exchange, as is the case with SDES.

The WebRTC specification [9] asserts that WebRTC implementations are required to support DTLS-SRTP for key management. Moreover, it is specified to be the default and preferred scheme, and there is no provision for other key management schemes to be implemented. In other words, other schemes may or may not be supported at all.

If an offer or "call" is received from a peer advertising support for both DTLS-SRTP and SDES, DTLS-SRTP must be selected - irrespective of whether the signalling is secured or not.

The Debate

It is generally accepted that DTLS-SRTP should be the mandatory and default option for the encryption of WebRTC media. What is being questioned is whether other mechanisms, namely SDES, should be utilised to provide backward compatibility.

From the compatibility perspective, Google's Chrome browser provides support for both SDES and DTLS-SRTP. Mozilla's Firefox on the other hand only implements DTLS-SRTP.

4.3.5. A Weakness in SRTP

SRTP only encrypts the payload of RTP packets, providing no encryption for the header. However, the header contains a variety of information which may be desirable to keep secret.

One such piece of information included in the RTP header is the audio-levels of the contained media data. Effectively, anyone who can see the SRTP packets can tell whether a user is speaking or not at any given time. Although the contents of the media itself remains secret to any eavesdropper, this is still a scary prospect. For example, Law enforcement officials could determine whether a user is communicating with a known bad guy.

4.4. Web-Based Peer Authentication & Identity Management

It is desirable for a user to be able to verify the identity of their peers. I.e. a user naturally wants to be certain that they are speaking to the person they believe that they are speaking to, and not an imposter.

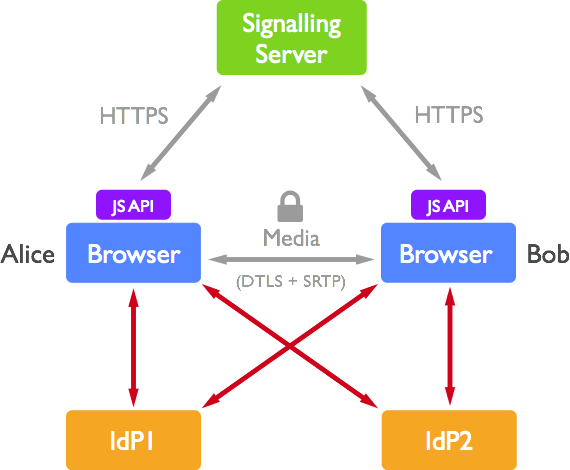

Although the signalling server may be able to go some way towards claiming a user's identity, the signalling server itself may not (and for the case of authentication SHOULD not) be trusted. We need to be able to perform authentication of our peers independently from the signalling server. This can be made possible through the use of identity providers.

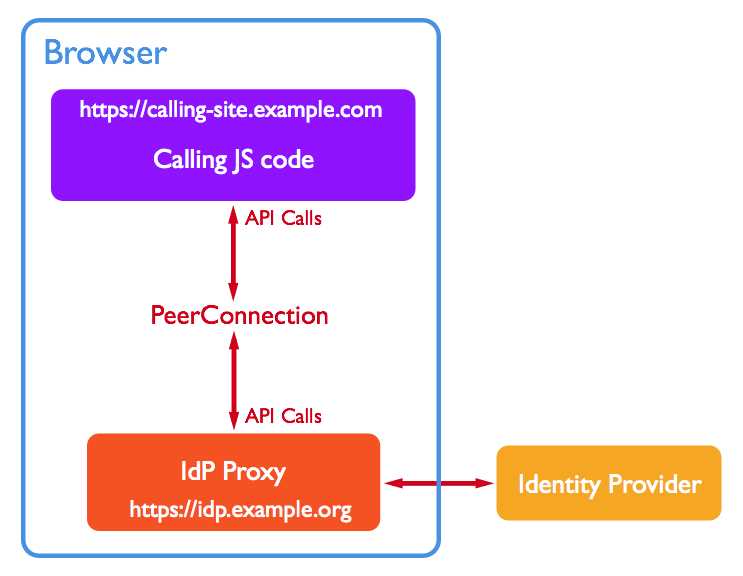

Figure 4. A call with IdP-based identity

A number of web-based identity providers (IdP) have recently become commonplace on the web, including Facebook Connect, BrowserID (by Mozilla), OAuth (by Twitter). The purpose of these mechanisms is simply to verify your identity to other services/users, on the authority of the identity provider itself. If a user has an account on Facebook then they can then use Facebook Connect, Facebook's IdP to prove to others that they are who they say they are on Facebook. This allows users to tie their authentication on other services to their main account on a "trusted" service. Note that in this case the level of "trust" that an Identity Provider possesses is subjective to the end-point user or service, and is often largely tied to user base and reputation across the World Wide Web.

The implementations of each IdP may differ due to independent development by different companies rather than being based on an open-source standard, but the underlying principle and functionality remains essentially the same. IdPs do not provide authentication for a signalling server; rather, they provide authentication for a user (and their browser through the process). WebRTC also places no requirements on which services should be used, and those which are utilised are based on the web application's implementation.

As the web application (calling site) is unrelated to this authentication process, it is important that the browser securely generates the input to the authentication process, and also securely displays the output on the web application. This process must not be able to be falsified or misrepresented by the web application.

Figure 5. The operation of an Identity Provider

4.5. IP Location Privacy

One adverse side-effect of using ICE is that a peer can learn one's IP address. As IP addresses are publicly registered with global authorities, they can reveal such details as a given peer's location. This could naturally have negative implications for a peer, which they would wish to avoid.

WebRTC is not designed with the intention of protecting a user from a malicious website which wants to learn this information. Typically, such a site will learn at least a user's server reflexive address from any HTTP transaction. Hiding the IP address from the server would require some kind of explicit privacy preserving mechanism on the client, and is out of scope of this report.

WebRTC does however provide a number of mechanisms which are intended to allow a web application to cooperate with the user to hide the user's IP address from the other side of the call. These mechanisms will be detailed in turn.

A WebRTC implementation is required to provide a mechanism to allow JS to suppress ICE negotiation until user has decided to answer the call. This provision assists end users in preventing a peer from learning their IP address if they elect not to answer a call. This has the side-effect of hiding whether a user is online or not to their peers.

The second such provision is that any implementation will provide a mechanism for the calling app's JavaScript to indicate that only TURN candidates are to be used. This can prevent a peer from learning one's IP address at all.

Furthermore, there is a mechanism for the calling app to reconfigure an existing call to add non-TURN candidates. Taken together with the previous provision, this allows ICE negotiation to start immediately upon an incoming call notification, thereby reducing delay, but also avoiding disclosing the user's IP address until they have decided to answer. This allows users to completely hide their IP address for the duration of the call.

References: [13]

4.6. Signalling Layer

As the signalling protocol is not specified by WebRTC, the mechanism for encryption obviously depends on the signalling protocol chosen. Due to the relatively open nature of signalling security, this report will focus on and briefly explain the of the most common protocol, SIP (Session Initiation Protocol).

SIP is a widely implemented standard used in VoIP communication to setup and tear down phone calls. However, it is a derivative of HTTP and SMTP - both are protocols that are regularly exploited. As it uses plain-text messages to exchange information, it is feasible for any malicious party to tap a network and capture SIP messages. If an attacker can read a user's sensitive information, they could use this information to spoof the user. And if the attacker can further proceed to gain access to the operator's network, it can even be possible for them to decipher the contents of WebRTC communication. [14]

Since SIP is sent in clear text, it is trivial for a determined attacker to intercept SIP messages. What happens next is left up to the imagination of the attacker, but it is not hard to imagine an eventuality in that the contents of the message body or header is tampered with. If the attacker intercepts an INVITE message, they may then proceed to change the FROM header to reflect his or her own IP address.

4.6.1. SIP Vulnerabilities

SIP is a communications protocol for signalling and controlling multimedia communication sessions and is frequently implemented in VoIP technologies for the purposes of setting up and tearing down phone calls. It can similarly be used in a WebRTC implementation for signalling purposes, as one of a number of possible such options. However, SIP messages are frequently sent in plain text. As this can naturally result in a number of potential attack vectors, we will take a closer examination of this area.

SIP Flow

In the process of setting up a call, a user's browser (or "User Agent") registers with a central registrar. This registration is a necessity in traditional VoIP as it is necessary to provide the means to locate and contact a remote party.

When a party (Bob) wants to initiate a call, he sends an INVITE message via a central proxy server (this is the signalling server). The server is responsible for relaying such messages, and providing the means to locate other users. The server may attempt a number of measures to locate an end-user during this lookup process, such as utilising DNS.

Registration Hijacking

The initial browser registration is used to announce a user's point of contact, and indicates that a user's device is accepting calls. However, the process provides a vector for malicious entities to perform a "Registration Hijack" attack.

The exchange of registration messages includes a "Contact:" field, containing the user's IP address. Whenever the signalling server processes an incoming call, the user name (or phone number) is matched up with the registered IP address, and the INVITE is forwarded accordingly. These registrations are periodically updated, ensuring the records are kept recent and up to date.

As SIP messages are always sent in plain text, it can be trivial for an attacker to intercept and read the contents of these registration messages. Following the interception, an appropriate tool (such as SiVuS Message generator) can be used to generate similar SIP information, but with the user's true IP address replaced by the attacker's own. The attacker then only has to disable the real user and send this information periodically to divert all incoming calls to themselves.

There are a number of methods that an attacker could utilise to disable a legitimate user, including: - Performing a DoS attack against the user's device - Deregistering the user (another attack which is not covered here) - Generating a registration race-condition, in which the attacker sends repeatedly REGISTER requests in a shorter timeframe (such as every 15 seconds) in order to override the legitimate user's registration request. This are all genuine risks to WebRTC signalling services.

As the implementation of SIP does not support the checking integrity of the message contents, modification and replay attacks are therefore not detected and are a feasible attack vector. This attack works even if the server requires authentication of user registration, as the attacker can once again capture, modify and replay messages as desired.

This attack can be suppressed by implementing SIPS (SIP over TLS) and authenticating SIP requests and responses (which can include integrity protection). In fact, the use of SIPS and the authentication of responses can suppress many associated attacks including eavesdropping and message or user impersonation.

Other possible attacks

MiTM attack

- If the attacker is able to intercept the initial SIP messages, he or she may then perform a MiTM attack.

Replay attack

- Captured packets could be replayed to the server by a malicious party, causing the server to call the original destination of a call. In other words, this would possibly take the form of a second unsolicited call request, identical to one the party had already received. Although a nuisance, the attacker would not be party of the call, as their IP information would not be included in the signalling packets.

Session hijacking

- Web servers are not stateful, with each request served a separate session (alleviates need for continuously authenticating). Cookies for authentication, but are nothing more than a data file containing the session ID. These cookies are sent by the web server to the browser upon initial access.

If the cookie were to be intercepted and copied, it could allow an interceptor full access to a session already in progress. In an attempt to mitigate this, most sites generate cookies using an algorithm involving user IP address and a timestamp to create a unique identifier.

Encryption

Although it may seem that signalling provides a particularly tempting vantage-point for attackers to target, all is not lost. In addition to the media streams, the signalling layer can also be encrypted. One such encrypted option is OnSIP, which uses SIP over Secure WebSockets (wss:// instead of ws://), with the WebSocket connection encrypted by TLS.

Although outside of this report's scope, other signalling technologies can similarly use TLS to encrypt their WebSocket or other web traffic. As with all encryption, if the third party does not know the secret encryption key, they are thereby unable to read the plain-text contents of the communication. This helps eliminate the risk of much of the above attack vectors, although it should be noted that the application programmer must specifically implement the encrypted signalling method for this to be applicable.

References: [16]

4.7. Additional Security Topics

Viewpoint of the Telecom Network

By providing support to WebRTC, a telecom network should reasonably expect not be exposed to increased security risk. However, devices or software in the hands of consumers will inevitably be compromised by malicious parties.

For this reason, all data received from untrusted sources (e.g. from consumer/users) must be validated, and the telecom network must assume that any data sent to the client will be obtained by malicious sources.

By adopting these two principles, a telecom provider must strive to make all reasonable attempts at protecting the consumer from their own mistakes that may compromise their own systems.

Cross-site scripting (XSS)

Cross-site scripting is a type vulnerability typically found in web applications (such as web browsers through breaches of browser security) that enables attackers to inject client-side script into Web pages viewed by other users. A cross-site scripting vulnerability may be used by attackers to bypass access controls such as the same origin policy.

Their effect may range from a petty nuisance to a significant security risk, depending on the sensitivity of the data handled by the vulnerable site and the nature of any security mitigation implemented by the site’s owner.

As the primary method for accessing WebRTC is expected to be using HTML5 enabled browsers there are specific security considerations concerning their use such as; protecting keys and sensitive data from cross-site scripting or cross-domain attacks, WebSocket use, iframe security, and other issues. Because the client software will be controlled by the user and because the browser does not, in most cases, run in a protected environment there are additional chances that the WebRTC client will become compromised. This means all data sent to the client could be exposed.

References: [17]

5. Comparison with competing/similar technologies

An examination of WebRTC's comparative security would fail to make sense without also considering the security of the competition. Fortunately for WebRTC, the competition in the web-based communication arena has its own share of issues.

This section will explore the comparative strengths and weaknesses of WebRTC and other platforms offering competing RTC functionality.

Some platforms we COULD explore are the following. The platforms to be explored have not yet been chosen. (To come after first-draft.)

Although widely relied upon, the additional installation processes can pose a barrier

- Flash

- Silverlight

- Jabber

- SIP

6. Secure design practices

WebRTC is built to be secure. However more than just blindly relying on the underlying technology, it is a good idea to consciously code with security in mind. This section will discuss coding practices that may be followed to ensure greater security over a vanilla WebRTC implementation. In particular, these practices could be applicable to organisations which expect to handle sensitive information, e.g. banking institutions, healthcare institutions or confidential corporate information.

Secure Signalling

As mentioned previously, WebRTC does not impose any constraints on the signalling process, rather leaving the developer to decide upon their own preferred method. Although this allows for a degree of flexibility that can have the WebRTC implementation tailored to the needs of the application, there can be risks associated with certain signalling protocols.

It is advisable to implement a signalling protocol that provides additional security, such as encryption of signalling traffic. By default, a signalling process may not incorporate any encryption, which can leave the contents of all exchanged signalling messages open to eavesdropping. Applications with a focus upon security/confidentiality should therefore ensure that their signalling layer is implemented over a secure protocol such as SIPS, OpenSIP, HTTPS or WSS.

Authentication and peer monitoring

A basic WebRTC app requires only a user's ID in order to perform a call, with no authentication performed from the view point of the service itself. It may be desirable to require pre-registration or authentication before any user can participate in a call. Unauthenticated entities should then be kept away from session’s reach, restricting accessibility to untrusted parties.

Since the media connections are P2P, the media contents (audio and video channels) are transmitted between peers directly in full duplex. Thus as the signalling server maintains the number of peers in communication, it could be consistently monitored for addition of suspicious peers in a call session. If the number of peers actually present on signalling server is more that the number of peers interacting on WebRTC page, then it could mean that someone is eavesdropping secretly and should be terminated from session access by force.

Permission Requests

It is a noted behaviour that often users will agree to permission requests or similar dialogs without consciously reading the message. This poses the risk of granting a web application with permissions which were not actually intended by the user.

Although this behaviour itself cannot be easily dealt with, one solution could be to clearly detail on the page what permissions the application will ask for. Such an application places a user's privacy at the forefront.

Man-In-The-Middle

In the eventuality that a malicious party succeeds in setting up a MiTM attack, there is typically not an easy solution to discover or fight against it. This is because the attack has no warning, and communication is allowed to proceed as normal. If one is not expecting such an attack, the attack will likely continue unnoticed.

However, by monitoring the media path regularly for no suspicious relays, we can take one small step towards mitigating against MiTM attacks. This should be coupled with encrypted signalling, as mentioned above.

Screen Sharing

An application offering any degree of screen-sharing functionality should have warnings in place to protect the user. As previously discussed, a user may not be aware of the extent of the screen being shared. Such an issue should fall back to a properly designed application to provide appropriate such information.

For example, before initiating the streaming of any part of the screen, the user should be properly notified and advised to close any screen containing sensitive information.

A Fallback

As a final fallback measure, we could venture as far as imagining a situation in that an active call session is compromised by a unauthorised party. If a call is confirmed to be compromised in such a way, it should be within the power of Web Application server rendering the WebRTC capable page to cut off the call.

References: [18]

7. Conclusion

In the modern age of smartphones and mobile devices people are communicating more than ever, and in even more personal ways than we have known before. Encryption in particular has become a big topic in recent years, following the growing awareness of major corporate hacking scandals and widespread government telecommunication eavesdropping. The result of which has been a rapid increase in user distrust of such organisations, and calls for arms in implementing greatly improved security measures. All the end user wants is to know that their personal data is kept private under control.

WebRTC has a big advantage over most VoIP services in the security area. Until now, most services have typically treated security as optional, meaning most end users use VoIP calls without encryption. Large corporations in particular are a leading culprit for this, choosing to save money on cheaper implementations rather than properly considering their users or the value of the data that they handle. But as WebRTC forbids unencrypted communication, users can be assured that their data remains safe and private.

Having been designed with security in mind, WebRTC enforces or encourages important security concepts in all main area. As such, as well as simply being built secure, it encourages WebRTC developers to also take their security seriously.

As a result of this strong focus on secure communication, WebRTC is currently regarded by some to be one of the most secure VoIP solutions out there. The main premise of having encryption by default is that a call is private at all times. Security and encryption are no longer considered to be optional features. And to round everything off, WebRTC is available free to everyone, providing a tempting and reliable framework for developers to build their next application.

In the near future we can expect to see more and more communication services providing greatly increased security to their users. But for now, WebRTC is one of those who are leading the charge.

References: [19]

8. Bibliography

1. RTCPeerConnection API Reference.

developer.mozilla.org. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

2. Brief Introduction to RTCPeerConnection API.

High Performance Browser Networking. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

3. SDP for the WebRTC.

tools.ietf.org. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

4. After signaling: using ICE to cope with NATs and firewalls.

html5rocks.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

5. Getting Started with WebRTC - Security.

html5rocks.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

6. WebRTC Security - Same Origin Policy.

tools.ietf.org. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

7. Security Considerations for WebRTC.

tools.ietf.org. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

8. Attack of the week: Datagram TLS.

blog.cryptographyengineering.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

9. Web Real-Time Communication (WebRTC): Media Transport and Use of RTP.

tools.ietf.org. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

10. The Foundation of WebRTC Security.

onsip.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

11. WebRTC MUST implement DTLS-SRTP but… MUST NOT implement SDES?.

webrtchacks.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

12. IETF-87 rtcweb agenda.

tools.ietf.org. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

13. Security Considerations for WebRTC.

www.ietf.org. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

14. WebRTC and Man in the Middle Attacks.

webrtchacks.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

15. Security in a SIP network: Identifying network attacks.

searchunifiedcommunications.techtarget.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

16. Two attacks against VoIP.

symantec.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

17. Security for WebRTC applications.

altanaitelecom.wordpress.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

18. WebRTC Security.

altanaitelecom.wordpress.com. Accessed on 2015-07-28.

19. Why WebRTC is the Most Secure VoIP Solution.

bloggeek.me. Accessed on 2015-07-28.